A Measure of Comfort (Cake and Cord)

2025

Wood (reclaimed), biochar, steel, water.

Photography by

Em McCann Zauder and

Peter Aaron/OTTO.

2025

Wood (reclaimed), biochar, steel, water.

Photography by

Em McCann Zauder and

Peter Aaron/OTTO.

The Olana Partnership

Olana State Historic Site

A Measure of Comfort (Cake and Cord) is a pair of interrelated sculptures installed on the former woodshed and ice house foundations in the Olana landscape. Historically, ice from Olana’s lake was cut and stored in blocks, or “cakes” for refrigeration, while wood from the estate’s planted forests was burned for heat. A Measure of Comfort reflects on these bygone methods of harvesting natural resources—wood and ice—for human comfort, while pointing to the challenge of maintaining control over temperature, and the peril to the environment in doing so, as we face climate change. Today we rely on advanced technologies to heat and cool instead of manual harvesting, and yet more than half of the energy used in homes is for heating and cooling. As climate change intensifies extreme weather events, the pursuit of comfort is increasingly urgent, prompting continued evolution in our technologies, but also a reassessment of our relationship with temperature and comfort. A Measure of Comfort explores this evolving relationship between people, nature, and climate systems.

On the site of the former woodshed, the sculpture consists of Southern yellow pine beams—remnants from a previous project—arranged vertically to form an uneven floor, or landscape. The volume of wood equals approximately one cord (128 cubic feet), referencing traditional firewood units that would be collected or purchased. Charred into the surface is the pattern of a decorative heating grill from the Olana house. Creating biochar in the process connects the work to the agricultural uses of the land that the woodshed foundation is a part of, and suggests one of the many ways forward towards a less carbon-intensive future.

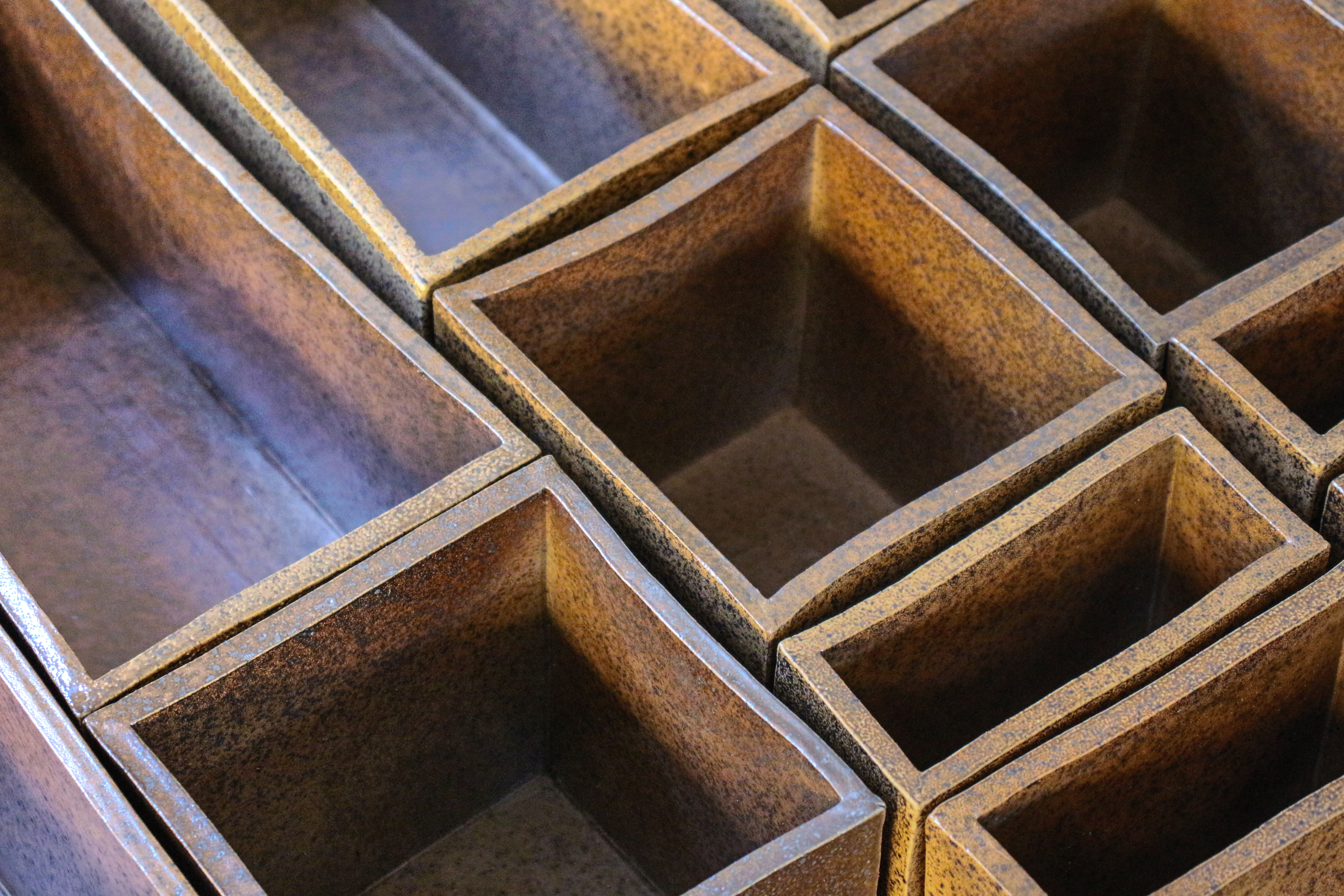

Contiguous with the history of managing the woods and planting trees at Olana is a record of ice harvesting on the lake, which used to freeze over regularly. At the ice house site, the sculpture reimagines a typical 19th-century ice “cake” through a series of reflective stainless steel water containers, descending in size. These containers will hold rainwater, naturally filling and evaporating over time. A mirrored stainless steel design, inspired by both the Hudson River watershed and rivulet patterns formed by melting ice, overlays the surface—invoking nature’s cycles and scales.

Together, the components of A Measure of Comfort (Cake and Cord) are an homage to historical and ongoing extractions of natural resources to satisfy human comfort. They call attention to the environmental ramifications of heating and cooling, and—as we see how our needs impact both the landscape and our shared world—urge us to consider how we might redesign systems and reassess our essential needs.

Olana State Historic Site

A Measure of Comfort (Cake and Cord) is a pair of interrelated sculptures installed on the former woodshed and ice house foundations in the Olana landscape. Historically, ice from Olana’s lake was cut and stored in blocks, or “cakes” for refrigeration, while wood from the estate’s planted forests was burned for heat. A Measure of Comfort reflects on these bygone methods of harvesting natural resources—wood and ice—for human comfort, while pointing to the challenge of maintaining control over temperature, and the peril to the environment in doing so, as we face climate change. Today we rely on advanced technologies to heat and cool instead of manual harvesting, and yet more than half of the energy used in homes is for heating and cooling. As climate change intensifies extreme weather events, the pursuit of comfort is increasingly urgent, prompting continued evolution in our technologies, but also a reassessment of our relationship with temperature and comfort. A Measure of Comfort explores this evolving relationship between people, nature, and climate systems.

On the site of the former woodshed, the sculpture consists of Southern yellow pine beams—remnants from a previous project—arranged vertically to form an uneven floor, or landscape. The volume of wood equals approximately one cord (128 cubic feet), referencing traditional firewood units that would be collected or purchased. Charred into the surface is the pattern of a decorative heating grill from the Olana house. Creating biochar in the process connects the work to the agricultural uses of the land that the woodshed foundation is a part of, and suggests one of the many ways forward towards a less carbon-intensive future.

Contiguous with the history of managing the woods and planting trees at Olana is a record of ice harvesting on the lake, which used to freeze over regularly. At the ice house site, the sculpture reimagines a typical 19th-century ice “cake” through a series of reflective stainless steel water containers, descending in size. These containers will hold rainwater, naturally filling and evaporating over time. A mirrored stainless steel design, inspired by both the Hudson River watershed and rivulet patterns formed by melting ice, overlays the surface—invoking nature’s cycles and scales.

Together, the components of A Measure of Comfort (Cake and Cord) are an homage to historical and ongoing extractions of natural resources to satisfy human comfort. They call attention to the environmental ramifications of heating and cooling, and—as we see how our needs impact both the landscape and our shared world—urge us to consider how we might redesign systems and reassess our essential needs.

Whether Shape or Break

2024

Photography by Brian Galderisi.

2024

Photography by Brian Galderisi.

The Korn Gallery

Drew University, NJ

Drew University, NJ

Reclamation (and Place, Puerto Rico)

2022

Wood, burlap, steel, asphalt, structural foam, coffee clay (used coffee grounds, flour, salt).

Photograpy by Sebastian Bach.

2022

Wood, burlap, steel, asphalt, structural foam, coffee clay (used coffee grounds, flour, salt).

Photograpy by Sebastian Bach.

no existe un mundo poshuracan:

Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria

Whitney Museum of American Art, NY

Organized by Marcela Guerrero.

Made specifically for the exhibition, "no existe un mundo poshuracán," this work takes the tools of my process for reclaiming used coffee grounds for an air dry clay—a process that includes drying, mixing, and forming—and reimagines them into a material landscape.

Historically, coffee is one of the Puerto Rican archipelago’s most significant crops, and was once cultivated by my grandparents. (My paternal grandparents, Joaquín and Toñita had a coffee farm near Ciales from the '50s - '70s; my paternal grandfather, Clery, was a horticulture professor in Mayagüez.)

The work suggests that reclaiming Puerto Rico’s agricultural independence in the name of past generations as well as those to come is a basic demand at the center of any rebuilding project for Puerto Rico. This autonomy is necessary to create food security, ecological sustainability, and climate resilience in Puerto Rico.

Reclamation—reclamación in Spanish—takes on layers of meaning that it lacks in English, to include a sense of demand or complaint. The work links this demand to both local and diasporic contexts, referencing elements of both Puerto Rican and New York infrastructure through its resemblances to the stilts of houses in the impoverished community of El Fanguito in San Juan, to mangrove roots, to the skyline, and to the hard but ever-shifting groundscape of New York City, where I was born.

Puerto Rican Art in the Wake of Hurricane Maria

Whitney Museum of American Art, NY

Organized by Marcela Guerrero.

Made specifically for the exhibition, "no existe un mundo poshuracán," this work takes the tools of my process for reclaiming used coffee grounds for an air dry clay—a process that includes drying, mixing, and forming—and reimagines them into a material landscape.

Historically, coffee is one of the Puerto Rican archipelago’s most significant crops, and was once cultivated by my grandparents. (My paternal grandparents, Joaquín and Toñita had a coffee farm near Ciales from the '50s - '70s; my paternal grandfather, Clery, was a horticulture professor in Mayagüez.)

The work suggests that reclaiming Puerto Rico’s agricultural independence in the name of past generations as well as those to come is a basic demand at the center of any rebuilding project for Puerto Rico. This autonomy is necessary to create food security, ecological sustainability, and climate resilience in Puerto Rico.

Reclamation—reclamación in Spanish—takes on layers of meaning that it lacks in English, to include a sense of demand or complaint. The work links this demand to both local and diasporic contexts, referencing elements of both Puerto Rican and New York infrastructure through its resemblances to the stilts of houses in the impoverished community of El Fanguito in San Juan, to mangrove roots, to the skyline, and to the hard but ever-shifting groundscape of New York City, where I was born.

— 2022

Low Relief for High Water

2021

Water-soluble paper, methyl cellulose, sandbags.

Photography by Sari Goodfriend and Nicole Salazar.

2021

Water-soluble paper, methyl cellulose, sandbags.

Photography by Sari Goodfriend and Nicole Salazar.

The Climate Museum

Presented in Washington Square Park, NYC

LOW RELIEF FOR HIGH WATER

is made of water-soluble paper

and methyl-cellulose,

a water-based non-toxic adhesive.

is cast from the windows of my childhood home,

an apartment in which I currently live, again,

on Manhattan Island, New York.

is vulnerable to water.

Over the course of a day,

I will take the work apart,

and give it to you.

In taking a piece of the work

—to care for, use, neglect, destroy—

you partake of the vulnerability

of our shared home, planet Earth,

and participate in our collective desire

to mobilize community for climate action.

GABRIELA SALAZAR, 2020 - 2021

LOW RELIEF FOR HIGH WATER was commissioned by the Climate Museum for the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, April 2020, and was postponed because of the global Covid-19 pandemic to October, 2021.

Presented in Washington Square Park, NYC

LOW RELIEF FOR HIGH WATER

is made of water-soluble paper

and methyl-cellulose,

a water-based non-toxic adhesive.

is cast from the windows of my childhood home,

an apartment in which I currently live, again,

on Manhattan Island, New York.

is vulnerable to water.

Over the course of a day,

I will take the work apart,

and give it to you.

In taking a piece of the work

—to care for, use, neglect, destroy—

you partake of the vulnerability

of our shared home, planet Earth,

and participate in our collective desire

to mobilize community for climate action.

GABRIELA SALAZAR, 2020 - 2021

LOW RELIEF FOR HIGH WATER was commissioned by the Climate Museum for the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, April 2020, and was postponed because of the global Covid-19 pandemic to October, 2021.

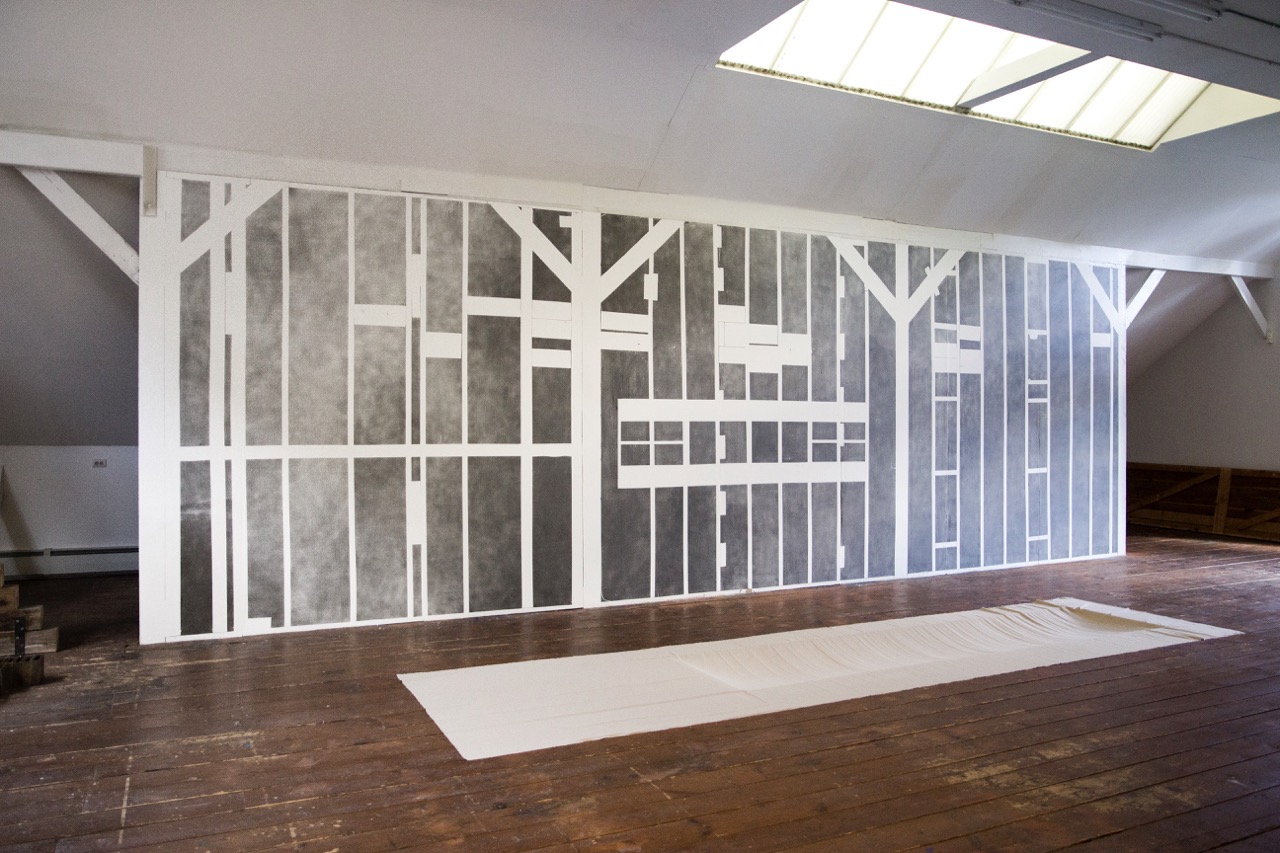

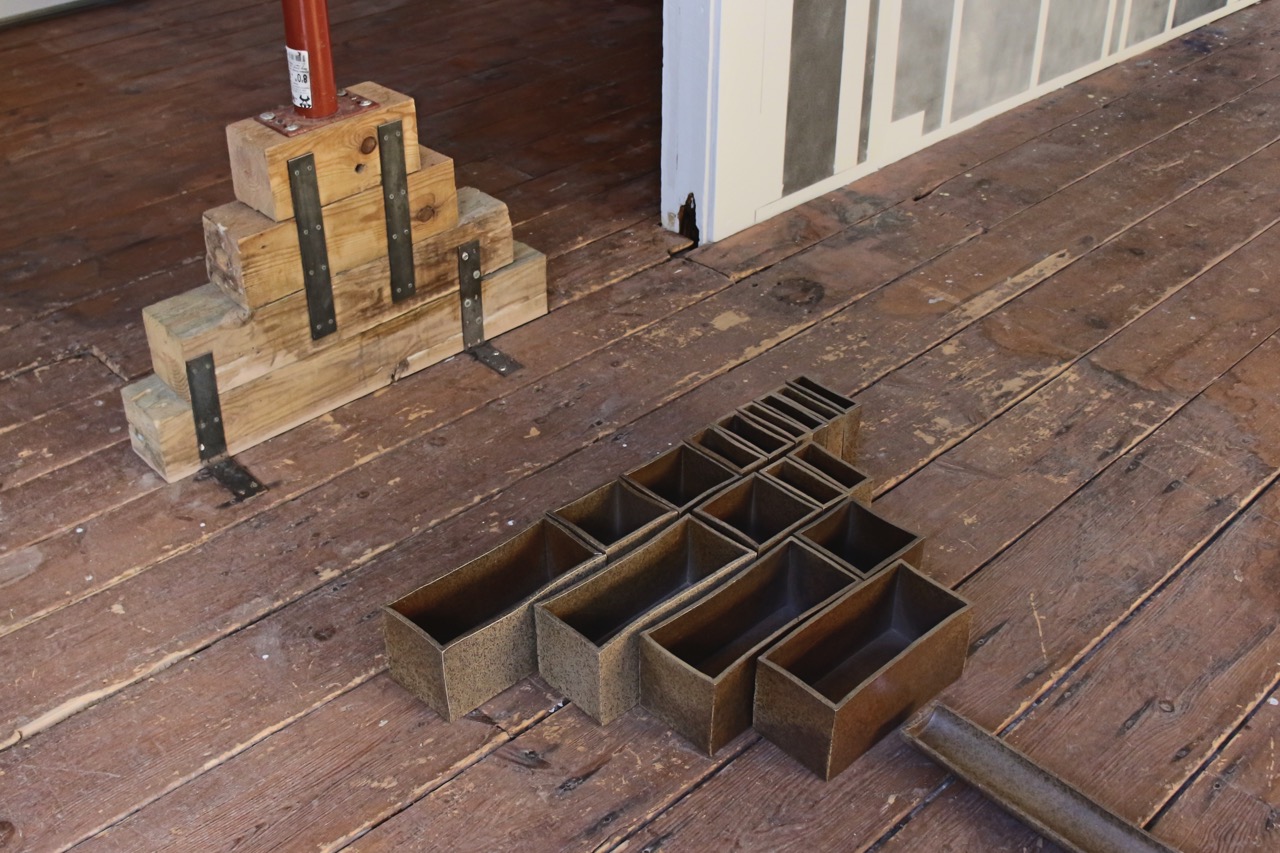

Holding Patterns

2021

2021

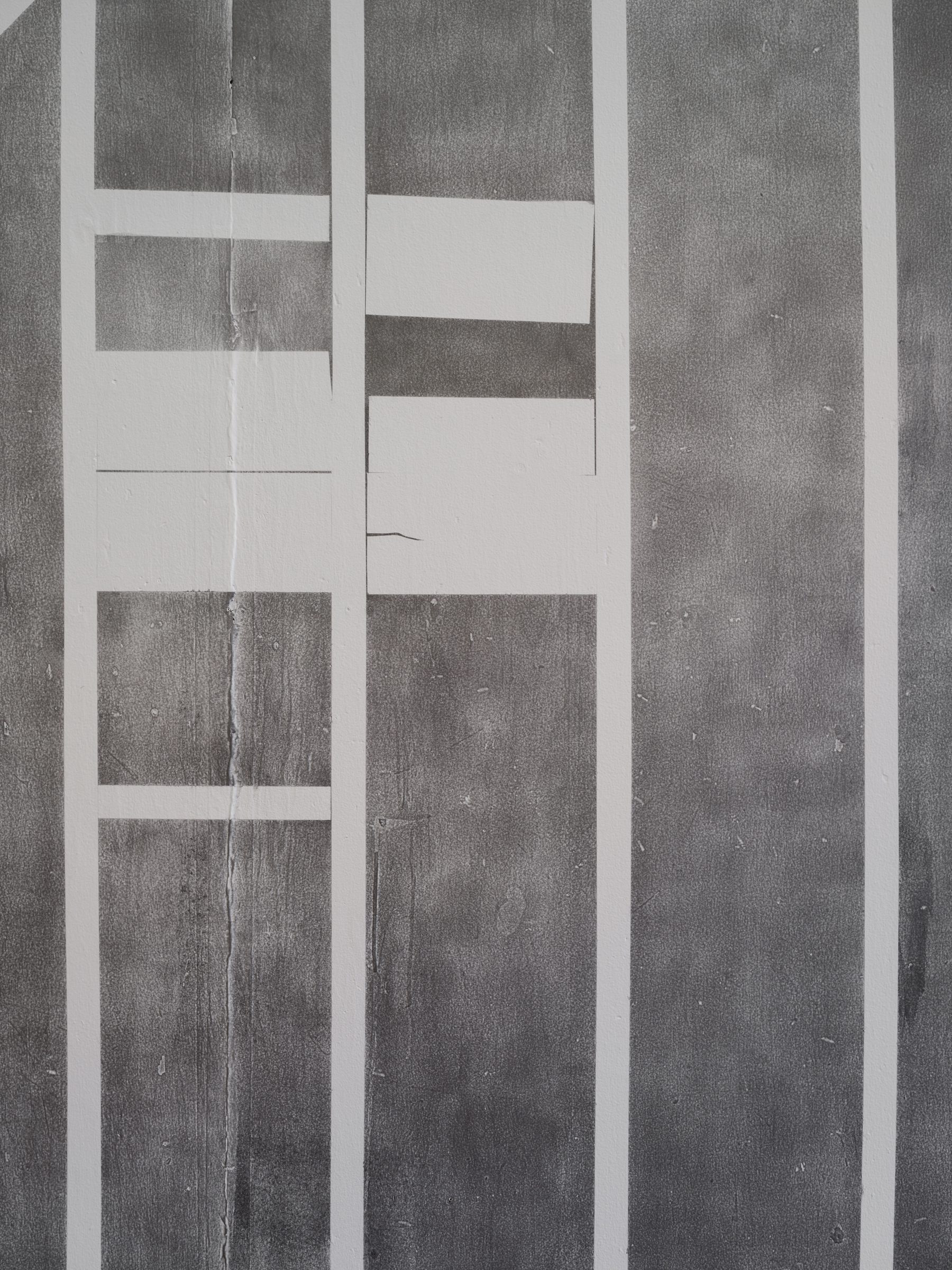

Holding Pattern, Walls (for Mara)

Existing studio walls, graphite powder.

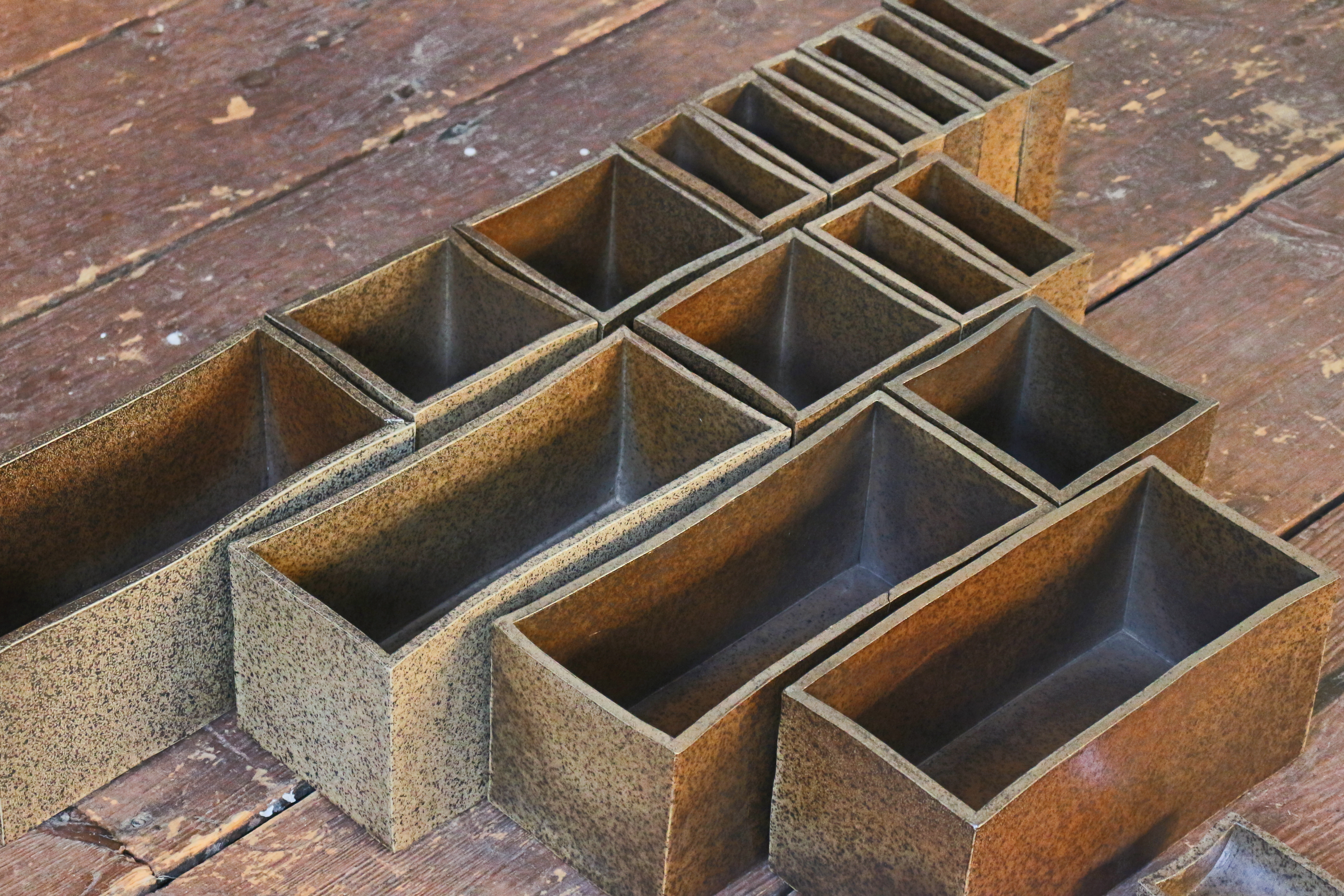

Holding Pattern, Column (for Gene)

Salt-fired ceramic.

Holding Pattern, Trapdoor (for Sylvia)

Linen, cotton thread.

Holding Pattern, Handrail (for Al)

Paper pulp, cardboard, wood, zinc handrail brackets.

River Valley Arts Collective at

The Al Held Foundation, NY

Through a series of interventions and sculptural objects, the artist transforms the exhibition site into an autobiographical drawing of itself. The exhibition is organized in collaboration with the Al Held Foundation in Boiceville, NY.

The site of intervention is a former hayloft modified by the abstract sculptor Sylvia Stone (1928–2011) who worked in the smaller of the two studios within Held’s Boiceville complex. To suit her practice, Stone added an oversized trap door in the floor to streamline the transport of large plexiglass and acrylic sheets used in her large-scale geometric works. The loft eventually became Held’s drawing studio in the latter part of his career when a connecting interior staircase was added and was subsequently used by the abstract painter Mara Held and is now reactivated by Salazar.

Through sculpture, drawing, writing, and site interventions, Salazar’s projects investigate the relationship between human-made spaces and structures and the unpredictable or invisible forces — the shifting of land, the pressures of gravity, the passing and layering of time and use — that act upon them. Ultimately, her work charts the psychic and physical effects of change. Salazar often uses found materials and sites, engaging in wordplay, psychogeography, and phenomenology to bring out new associations between the found, the altered, and the made.

The main component of Salazar’s presentation is a one-to-one drawing of the negative space created by the behind-the-scenes wall studs and cleats of the studio’s two facing walls. Applying graphite powder directly onto the walls’ external surface, Salazar produces an off-kilter grid through the act of transference of the interior structure. Conceived as a collaborative drawing that considers the studio’s past occupants, the work incorporates the underlying structure as it compounds history of the walls’ use by making visible the subtleties that layers of white paint aim to hide: remaining traces of wall spackle, surface grain, fingerprints, protrusions and dents. By revealing this past use of the wall surface, the work draws attention to its literal make and measure and serves as a kind of map of the history of the room and how it came to be.

Further drawing on the architecture of the site — the trap door, support column, and hand rail — the artist considers the psychic space and the physical mechanics of holding through sculptural interventions. Pointedly, the textile, paper pulp, and salt-fired ceramic works perform a mimesis — an imitation of the room’s structural forms and architecture — as they embody a constellation of ideas Salazar formed around the notion of holding and to hold; conceptually tying together the use of the studio-as-surface/container/repository, the geographical proximity of the Ashokhan Reservoir, an on-site ceramic silo, the act of filling and draining, the dramatic relocation of Boiceville, the water system that supplies New York City, the artist’s own upbringing and motherhood, sustenance, support, commitment, resentment, containment, transference, osmosis, preparedness, life and death.

The Al Held Foundation, NY

Through a series of interventions and sculptural objects, the artist transforms the exhibition site into an autobiographical drawing of itself. The exhibition is organized in collaboration with the Al Held Foundation in Boiceville, NY.

The site of intervention is a former hayloft modified by the abstract sculptor Sylvia Stone (1928–2011) who worked in the smaller of the two studios within Held’s Boiceville complex. To suit her practice, Stone added an oversized trap door in the floor to streamline the transport of large plexiglass and acrylic sheets used in her large-scale geometric works. The loft eventually became Held’s drawing studio in the latter part of his career when a connecting interior staircase was added and was subsequently used by the abstract painter Mara Held and is now reactivated by Salazar.

Through sculpture, drawing, writing, and site interventions, Salazar’s projects investigate the relationship between human-made spaces and structures and the unpredictable or invisible forces — the shifting of land, the pressures of gravity, the passing and layering of time and use — that act upon them. Ultimately, her work charts the psychic and physical effects of change. Salazar often uses found materials and sites, engaging in wordplay, psychogeography, and phenomenology to bring out new associations between the found, the altered, and the made.

The main component of Salazar’s presentation is a one-to-one drawing of the negative space created by the behind-the-scenes wall studs and cleats of the studio’s two facing walls. Applying graphite powder directly onto the walls’ external surface, Salazar produces an off-kilter grid through the act of transference of the interior structure. Conceived as a collaborative drawing that considers the studio’s past occupants, the work incorporates the underlying structure as it compounds history of the walls’ use by making visible the subtleties that layers of white paint aim to hide: remaining traces of wall spackle, surface grain, fingerprints, protrusions and dents. By revealing this past use of the wall surface, the work draws attention to its literal make and measure and serves as a kind of map of the history of the room and how it came to be.

Further drawing on the architecture of the site — the trap door, support column, and hand rail — the artist considers the psychic space and the physical mechanics of holding through sculptural interventions. Pointedly, the textile, paper pulp, and salt-fired ceramic works perform a mimesis — an imitation of the room’s structural forms and architecture — as they embody a constellation of ideas Salazar formed around the notion of holding and to hold; conceptually tying together the use of the studio-as-surface/container/repository, the geographical proximity of the Ashokhan Reservoir, an on-site ceramic silo, the act of filling and draining, the dramatic relocation of Boiceville, the water system that supplies New York City, the artist’s own upbringing and motherhood, sustenance, support, commitment, resentment, containment, transference, osmosis, preparedness, life and death.

— Olga Dekalo, 2021